At a certain point as you navigate the Pinellas Bayway in the dark into St. Petersburg Beach, Florida, the lustrous shine of the magnificent 73 year-old Don Cesar Hotel fills your car’s windshield and commands your vision. The points of the hotel’s Moorish minuets frame the sky with emphasis, silently communicating that you have arrived. Even if you lack a skilled imagination, you have absolutely no problem envisioning that the “Pink Castle” – as The Don Cesar is called – hosted F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, the Bloomingdales, and the 1930’s New York Yankees’ spring training teams, led by The Great Bambino himself. What was harder to understand and less obvious to me was how just two miles up the road the penultimate Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Florida was being converted into a generic Caribbean cafe. The ridiculous sense of urgency I felt the entire 500 mile drive from Atlanta was not unfounded because, as it turned out, the restaurant’s menu was being replaced and floorboards were literally being torn up as I drove.

sky with emphasis, silently communicating that you have arrived. Even if you lack a skilled imagination, you have absolutely no problem envisioning that the “Pink Castle” – as The Don Cesar is called – hosted F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, the Bloomingdales, and the 1930’s New York Yankees’ spring training teams, led by The Great Bambino himself. What was harder to understand and less obvious to me was how just two miles up the road the penultimate Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Florida was being converted into a generic Caribbean cafe. The ridiculous sense of urgency I felt the entire 500 mile drive from Atlanta was not unfounded because, as it turned out, the restaurant’s menu was being replaced and floorboards were literally being torn up as I drove.

It had been over twenty-five years since I last visited the Hojo’s in St. Pete Beach. It was the destination of the last of my family’s annual summer driving trips from New Jersey to Florida. For ten years in a row, the seven of us had crammed into first, a 1968 Oldsmobile sedan and then, a late 1970’s Ford station wagon, for the excursion from the urban heart of the Northeast to the Sun Coast.

While the Don Cesar is sculpted in an art gallery area at the south end of the beach called “Pass-A-Grille,” the Hojo’s was erected in the middle of the working class strip – surrounded by a Sandpiper Hotel on one side and a Best Western on the other. The “HJ” (as my family called it), was all you could have asked for in an affordable motel: it was located directly on the Gulf of Mexico and had a game room, pool, kiddie pool and shuffleboard courts. Mini-golf, cheap T-shirt and souvenir shops and a 7-Eleven were within walking distance. What the motel didn’t offer, such as tennis courts, was graciously provided free of charge by the comparatively elegant Breckenridge Hotel two doors down. During the laissez-faire 70’s, my brother and I could easily slip onto the Breckenridge’s courts; after we were good and sweaty, two hours of tennis in 97 degree heat was followed by a quick dip in The Breckenridge’s pool (our stringy, dungaree cut-off shorts tipping off the upscale European guests that we belonged in the pool several doors down).

The impetus for my trip to St. Pete was the realization that the Howard Johnson’s restaurants – all of them – had nearly disappeared. As of January 2009, only 3 Howard Johnson’s restaurants remained in the entire country. At its height in the late 1970’s, there were approximately 1000 Howard Johnson’s restaurants and 500 motor lodges throughout the United States. To provide some perspective, an Amoco guide map from 1978 lists 94 Howard Johnson’s motels in Florida alone.

The St. Pete motor lodge was the classic, late 1960’s Howard Johnson’s design, consisting of a “Gatehouse” motor lobby (which housed the hotel’s registration desk and sundries store) and separate restaurant, both with a brilliant orange roof. The Gatehouse was a two-story building, with triangular, pointed sides, while the restaurant was a long, single story structure with a slanted roof and large picture windows. Both buildings sported cupolas, with white fins at the base, topped by a turquoise pyramid with a “Simple Simon and the Pieman” weathervane. The Simple Simon and the Pieman logo appeared on signs, menus and china patterns throughout the roadside empire.

What we did at the St. Pete Hojo was, at the time, happening at hundreds of Hojo’s around the country. There was the pool, with a diving board and/or twisting slide. There was pinball and ping pong in the game room while you dried off from a day at the beach and munched on Lance vending machine snacks. For dinner, there was the Hojo restaurant. For the kids, a grilled, buttered frankfurter in a square toasted bun, served in a cardboard “boat” container, followed by a massive ice cream sundae piled high in a clear goblet and crowned with a Hojo sugar cookie. Adults often opted for the Friday night “$2.99 All You Can Eat Fish Fry” or a generous plate of “tendersweet” clams. And if that wasn’t enough (which it wasn’t), on the way out, the kids picked up fudge candy bars or Hojo Fruit Gum to munch on later in the room while they stayed up past their usual bedtimes to play cards and watch incredulously as Sophie Loren laughed at Frank Gorshin’s impersonation of Jimmy Cagney on The Tonight Show.

Even a bad childhood memory did not diminish the great feelings I still had. On one of the first trips to St. Pete, I cut my toe in the motel pool and it wouldn’t stop bleeding. As my father un-wrapped the third blood-soaked towel from my foot, the worry on his face reflected the helplessness that surprisingly had sprung up from the chlorinated water.

The addition of a new facade and some painting aside, the demise of the restaurant was the biggest change I noticed at the St. Pete Hojo’s. Subtle remnants from my childhood trips were still in place in the motel room, but likely overlooked by the casual traveler. My personal favorite was the two-pronged metal hook hanging in the bathroom. This used to hold two faux linen, scratchy “Shoe Shiner” cloths that, as printed on the Shoe Shiners themselves, could also be used to “clean your razor, remove your cosmetics (!) or clean your eyeglasses.” I cannot imagine a Spa Girl of the 2000s removing her make-up with a cloth that’s strong enough to strip a razor clean.

Other things hadn’t changed at all; over the course of several days, mini-vans and cars pulled up outside my first floor patio and discharged Northeastern, Midwestern and Canadian families, the kids swinging doors open and scurrying towards the pool as soon as the vehicles came to a full stop.

“From Maine to Florida” was Howard Johnson’s slogan for a time during the 1960’s. I’ve stayed in HJ’s from Massachusetts to Florida. Ones I can immediately recall are Albany, New York, Williamsburg, Virginia, Hardeeville, South Carolina, Lauderdale By the Sea, Florida, and my hometown, Clark, New Jersey. The Howard Johnson’s in Clark was located on what later became prime real estate just off Exit 135 of the Garden State Parkway. The curved exit ramp practically forced vehicles leaving the Parkway into the HJ’s parking lot, like steel balls on a pinball groove. Word around town among men my father’s age was that “Villa” owned all the land in the township on that side of the Parkway and had made a killing leasing a precious plot to Howard Johnson’s. The HJ was within spitting distance of a ball bearing manufacturing plant and across the street from a Pathmark Supermarket and Grant’s Department Store. Spread across over 20 acres, the motor lodge and restaurant sat in stark contrast to the modern Hampton Inns, Super 8 Motels, and Red Roof Inns, which are shoe-horned into 5 acres between a gas station and a Cracker Barrel.

The 1960 Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge Directory boasts of the Clark HJ’s proximity to the “Clark Industrial Park,” which, before the advent of environmental sensitivity, was a good thing. What I always remember about the Clark HJ was the 50-foot high, two-sided road sign planted alongside the Parkway. The top of the sign was shaped like the top of a Howard Johnson’s restaurant – long orange roof, white fins and turquoise cupola. Either coming back from a visit to New York City, a high school track meet, or a family vacation in Florida, the HJ sign told me I had made it home. In fact, because of the way the rotary had been constructed, we passed the HJ every time we exited the Parkway, regardless of the direction we had come from. That lent credence to my grandfather’s claim that he stopped in for a hot dog and butter pecan ice cream every time he came to town to visit.

As evidenced in Clark day after day, one of the best-kept secrets about America’s greatest roadside chain was that although its wingspan was interstate, its heart and soul was local. While F. Scott and Zelda drank at the Don Cesar in bliss, Alcoholic Anonymous members at the East Norwalk, Connecticut Hojo’s searched the Simple Simon and Pie Man coffee cup cradled in their hands for fortitude. Though you stayed at the Hardeeville, South Carolina lodge nestled off a lonely I-95 exit ramp on your way to Florida, your mother brought you to the Worcester, Massachusetts location you walked past everyday on your way home from school as a reward for getting A’s and B’s on your report card.

Though exhausted fathers and truck drivers fueled up on piping hot black coffee at one of the many HJ’s along the embarrassingly HJ-rich Delaware Turnpike, hyperactive children celebrated birthdays with parties at the Hojo’s in their hometown with a free cake and a birthday card signed by Howard B. Johnson himself.

In Albany, New York, the HJ cocktail lounge – which had morphed from a Red Coach Grill into a “RumRunners” Bar and Grill – entertained the twenty-something set with a rock band, $1 drafts and a Bowl-A-Matic 3000 game. The scene in Albany wasn’t much different from the Ground Round – a Howard Johnson’s owned spin-off – on Route 22 in New Jersey where I went to watch my co-worker from the nail polish factory play drums in a band. The three-man group imitated their idols in Rush while I and other patrons, following established Ground Round custom, pelted them in the head with peanut shells and popcorn.

The HJ didn’t discriminate. The restaurant welcomed the happy hour folks and traveling salesmen who walked down the back hallway, past the “Local Attractions” brochure rack, and slipped into the cocktail lounge through the discrete restaurant entrance. Often identified by a lighted “Cocktail Lounge” sign, the entryway could have doubled for a men’s room door. As a pre-teen peering through the opening, I found the mixture of darkness, smoke and neon beer sign lights far more intriguing than any of the dinosaur museums or Revolutionary War battlefield tours advertised in the free brochures.

The peculiar history of the local Howard Johnson’s more often than not will also tell you the tale of the town itself, the all-glass front of the restaurant offering an unobstructed view. Take the one in Clark, for example. In 1960, as a traveler to or a resident of the burgeoning Newark suburb, you were welcomed at the registration desk by your “Host, Matthew Minnicino.” By the mid-1980’s, mirroring the corporate expansion and “crane and chain” landscape that was emerging in the area, H-J Holding Company, “an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Imperial Group Limited, a publicly traded English company headquartered in London,” had taken over the Clark business license. During the Holding Company era, the parking lot filled with plush charter coaches bound for the newly minted casinos in Atlantic City. For a nominal fare, the same people who had ten and twenty years before driven their children 27 hours away to the Vero Beach or Lake Buena Vista, Florida HJ’s for vacation, were now effortlessly transported only an hour or so away to a $3.99 prime rib buffet and $20 worth of complimentary chips, courtesy of Mr. Donald Trump.

Meanwhile, word leaked from Wall Street that the primary impetus for the British company’s Hojo acquisition was not to restore the chain to glory but that the undervalued strategic locations of the HJ’s real estate were too cheap to pass up. The Clark Howard Johnson’s was eventually bulldozed and replaced with a ShopRite Supermarket, the old ShopRite down the street having been razed and replaced with a Barnes & Noble Superstore and a Chili’s.

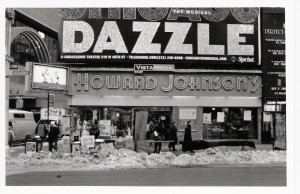

If you think I’m overstating the correlation between the HJ’s and their surrounding locale, consider 2 of the last 10 restaurant locations: Times Square and Asbury Park, NJ. Located 22 miles from where the Clark HJ once stood, the 50-year old institution at the corner of Broadway and 46th Street closed several years ago. As Times Square was rejuvenated, the retail space became too valuable to keep as a Howard Johnson’s.

The Asbury HJ, the last Howard Johnson’s restaurant in New Jersey, had remained open for business on the famed boardwalk until it closed in 2006. Unlike in Times Square, the total re-development of Asbury’s waterfront, which has been promised for decades, has still not occurred. Something of a marvel in the world of boardwalk and roadside culture, the space-aged designed restaurant has anchored the Asbury boardwalk since the late 1950’s. It was a two-story, cylindrical-shaped building with a multi-pointed roof; a red railing and circular ramp wrapped around it like a band of fire. It was a flying saucer dropped from the sky in the middle of a linear park filled with frozen custard stands, betting wheels and whirling teacups. It served the weekenders who brought their children for a day at the beach and some ice cream, and the locals, including my grandmother during the 1960’s and 70’s, with live music upstairs in the cocktail lounge on Thursdays night.

I visited both sites just prior to their closures. At the Times Square Hojo, tourists and aficionados wandered in for a taste of the past, many conscious of the impending doom. Outside the Asbury Hojo, two gypsy women gathered their possessions and slowly headed for the bus stop; their children ran down the walkway ramp that took them out of the sunlight and into the shadows created by the shell of a mid-rise condo building, forever suspended in an early stage of construction. The town of Asbury Park patiently awaits the revival that has come to Times Square. In a cruel twist that, in many ways, defines the thirty-year re-development efforts, the Asbury Hojo’s was closed to make room for million dollar seaside residencies whose construction has once again been suspended. The Asbury HJ survived the Apocalypse, but it did not survive the promised Renaissance.

As Times Square and Asbury show, the truth lies not in what has left, but in what has been left behind. If Times Square is nostalgia, Asbury is haunting nostalgia.

As strange as it may seem, the Times Square and Asbury Park Howard Johnson’s have had it much better than most of their sisters. An unseemly fate for many Hojo restaurants is their transformation into a motel affiliated with an inferior chain (the brilliant orange roof being smeared into the mediocre yellow of a Days Inn), or, even worse, into a different eatery altogether. Common conversions of HJ restaurants include new concept eateries (such as a “Scotch & Sirloin” in Wallingford, Connecticut) or private establishments (“The Purple Onion” in Benton Harbor, Michigan or “Riviera Family Restaurant” in Columbus, Indiana), or even a gas station and convenience store (“Gators” off I-75 in central Florida).

At www.hojoland.homestead.com, a website devoted to all-things Howard Johnson’s, these transmuted HJ’s are referred to as “ghosts.” The Hojo Intelligentsia send in photos from around the country, and the website records the degradation.

My own research indicates that a surprising number of Howard Johnson’s restaurants have become strip clubs. One I passed didn’t even bother to make any structural changes to the building; simply painted black and gold, with opaque windows, it was called “Players – Adult Entertainment.”

At another former HJ location in the Southeast, a nude dance club took over the restaurant building while the adjacent motel became a Days Inn. The pool area there is a war zone. Emptied years ago, the hollow, cement pond has become a landfill for unwanted objects. The diving board, ripped from its anchors at the head of the S-shaped pool years before, undoubtedly due to liability concerns, is likely buried at the bottom of the rumble. A row of rooms originally constructed with back patios that offered a scenic overlook for the pool now served primarily as the launching pad for the trash heap. The projectile pitchers who inhabit these rooms are situated adjacent to the strip club parking lot. Hypocritically, they make the most of their location by eavesdropping on raucous conversations or hawking departing employees late into the night, but then curse the rowdy setting when it finally comes time to be put to bed.

“America’s Landmark — Under the Orange Roof,” another great Howard Johnson’s tribute site located at www.highwayhost.org, maintains a running tally of the remaining restaurants. Which one will be the last one standing is anybody’s guess. What we’re left with makes us like a neglected long-term care patient stranded in the Neverland of a nursing home bed; after many years of tolerating Ensure and crackers, we have a craving for juicy peaches and tender filet mignon. Sure, we want that last taste, but we’re praying for something more. Orange roofed-ice cream parlors – designed especially for kids – have become perverted playlands for prowling adults, concealed in black and gold paint. The hearts and souls of our towns and cities have been obliterated, yet we’re still tethered to that past, like the nursing home guest to her oxygen cart. As clear as the roadside signs which used to direct us home, there are ghosts all around us, but no one is doing a damn thing about it.